Increased hunter success across the board in fall 2024 should be chalked up as a win.

Here’s a story worth celebrating.

BOISE, ID – Big game hunters apparently got after it in the fall of 2024, accomplishing a statewide hat trick of harvest increases—the first time since 2020—of elk, mule deer, and white-tailed deer. Hunters are no strangers to swings in populations and harvests, and Idaho Fish and Game wildlife biologists highlight that each year; there are a lot of contributing factors. But last year’s hunter harvest is a hopeful indicator that herds are once again back on track.

Not to harken back and beat a frozen horse, but it always helps to put things into perspective in regard to the brutal winter of 2022-23. That winter didn’t just leave its mark in the record books, it greatly impacted mule deer herds in Idaho. The hunting season that followed some six months later came as no surprise as statewide harvests dropped.

But fast forward to 2024—a year that granted Idaho’s deer and elk some much-needed reprieve from harsh winter weather—and now we could be starting to see the dawn of greener pastures for both big game and big game hunters alike.

It’s still a little early for biologists to read the tea leaves and know how the 2024-25 winter survival will affect this fall’s hunts, so stayed tuned for more on that down the road.

But moral of this story? Increased hunter success across the board in fall 2024 should be chalked up as a win. After all, hunters can’t harvest animals that aren’t there.

Harvest highs and lows (but mostly highs)

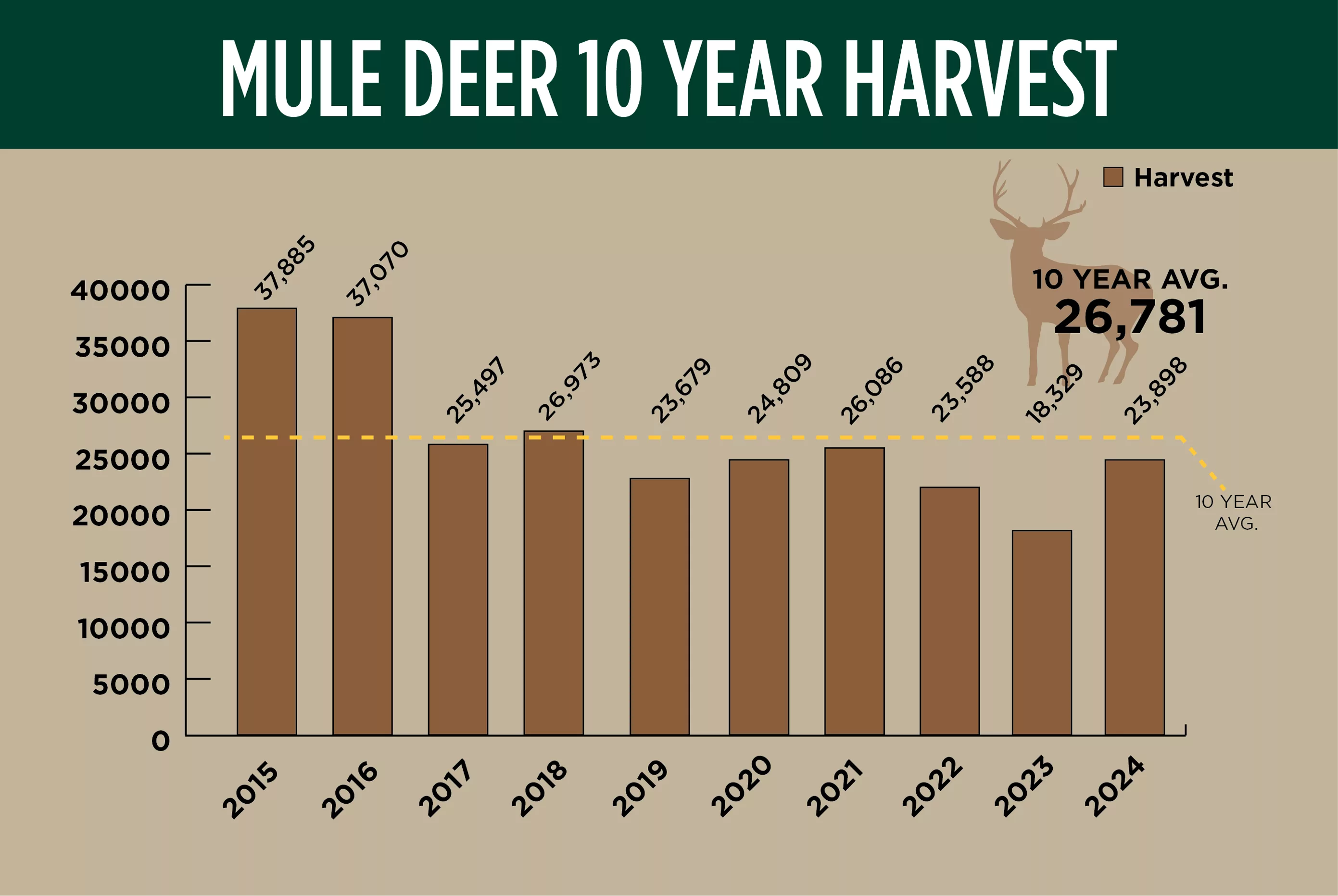

Like I said earlier, there’s not too much to go over in the “lows” department since harvest of all three species increased, but let’s start with mule deer this time, since they were the tragic stars of the dramatic 2023 winter. After a 22% drop in harvest (remember, these numbers are statewide) from 2022 to 2023, it was enough to put a smile on any mule deer hunter’s face to see that number go from 18,568 to 23,898 in the fall of ’24.

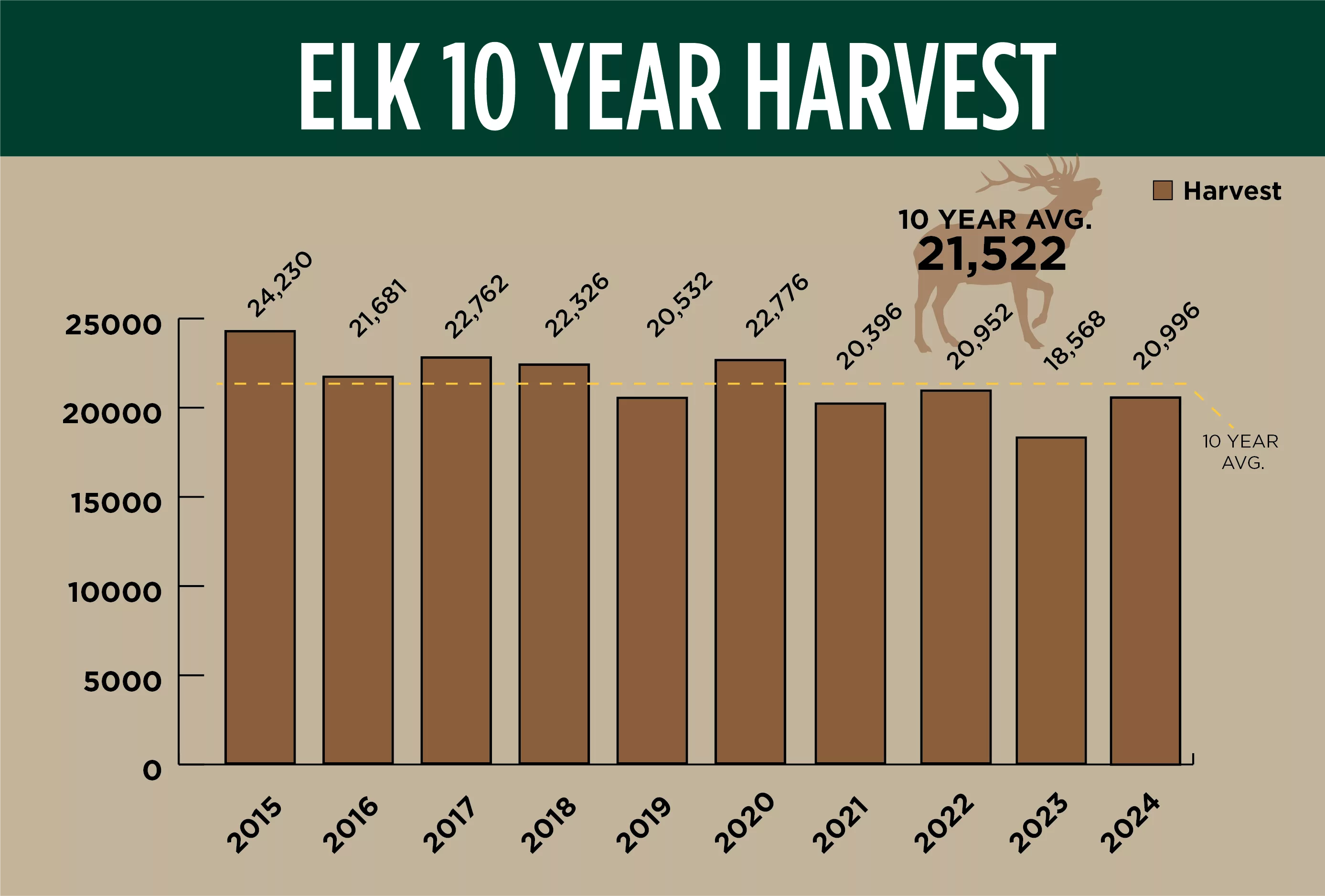

And elk were no different. While the stalwarts of the mountains didn’t necessarily see the same impacts of that brutal winter as their smaller, long-eared cousins, elk harvest in 2024 still rose roughly 13% from the previous year. Nearly a quarter of all general season elk hunters last year successfully hiked out of the mountains with an elk on their back, a statistic also slightly up from the previous hunting season.

This year’s harvest landed at 97.5% of the 10-year average, which makes it about as close to a “normal” harvest as you can get with fluctuating annual harvests.What about whitetails? What were they up to last fall? Well, I’m glad you asked.

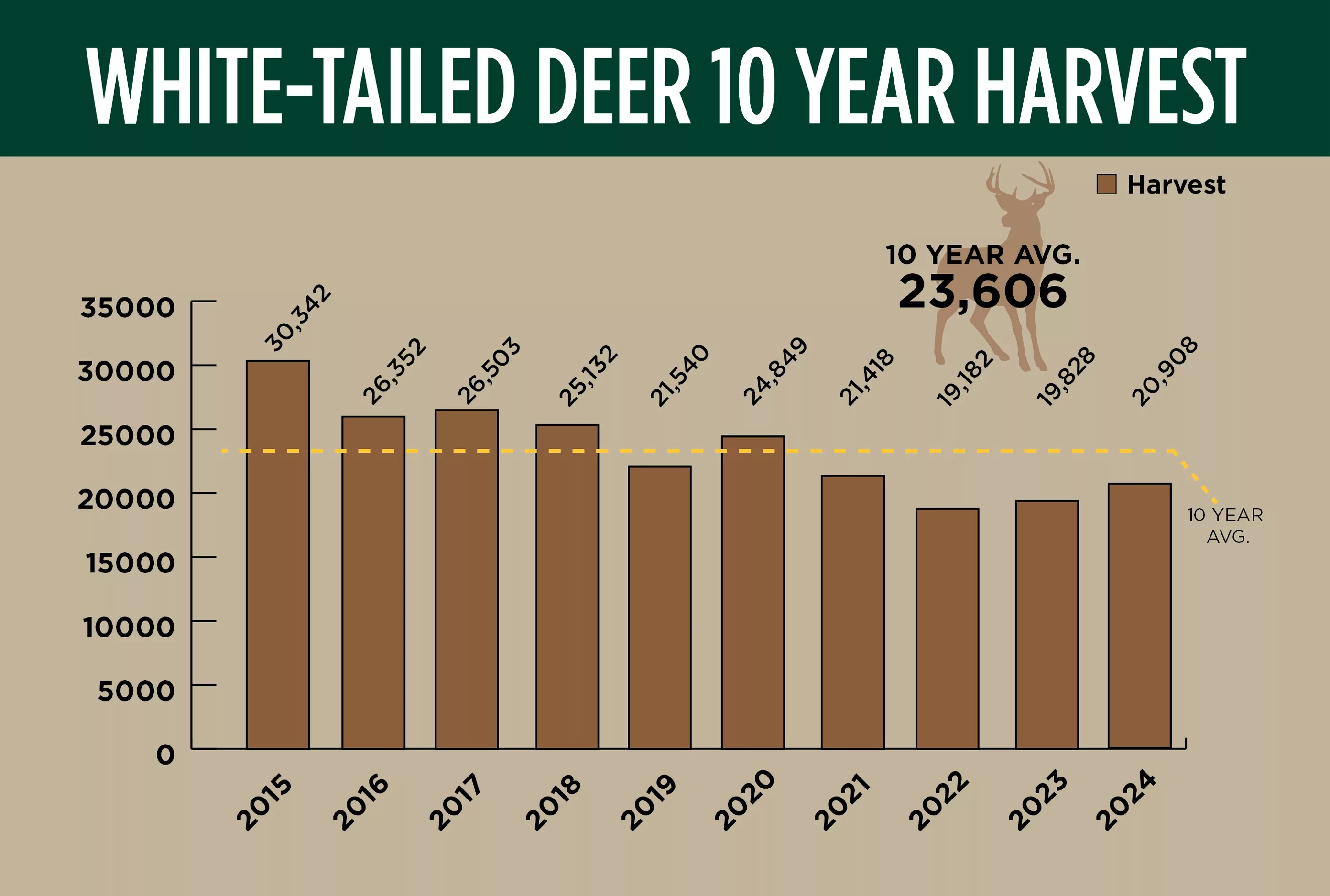

White-tailed deer represented the only “X” in the win column back in 2023’s hunter harvest report, where the primary “W” word was winter, not whitetails. But for the last two years now, white-tailed deer harvests have kept pushing the needle clockwise, accounting for roughly a 9% bump since 2022. In 2024, roughly 48,766 white-tailed deer hunters took home an estimated 20,908 whitetails statewide.

ELK

By the numbers

Total elk harvest in 2024: 20,996

2023 harvest total: 18,568

Overall hunter success rate: 24%

Antlered: 12,610

Antlerless: 8,390

Taken during general hunts: 13,170 (19% success rate)

Taken during controlled hunts: 7,830 (42% success rate)

How it stacks up

If you recall, the drop in 2023 elk harvest was a bit of a head-scratcher. Anecdotally, Fish and Game heard reports from experienced elk hunters who were not finding elk in their usual spots during fall and suspected that maybe a combination of hot temperatures and scant precipitation might have been a significant factor. Toby Boudreau, Fish and Game’s Deer and Elk Coordinator, stated that the dip in statewide harvest did not reflect a dip in the overall elk population, but it would possibly take another year to know for sure.

A year later, that’s exactly where we’re at, and Fish and Game biologists believe the statewide elk population is healthy and relatively stable.

“While things vary from elk zone to elk zone, statewide elk populations tend to stay relatively stable from year to year, and last year’s drop combined with this year’s increase in harvest is right in line with the seasonal fluctuations,” said Boudreau.

Additionally, general season hunter success crept up a little to 19%, which is right on par with previous years, while controlled hunt success shot back up to 42% success rate from last year’s 23%.

MULE DEER

By the numbers

Total mule deer harvest in 2024: 23,898

2023 harvest total: 18,329

Overall hunter success rate: 32%

Antlered: 20,515

Antlerless: 3,380

Taken during general hunts: 17,940 (28% success rate)

Taken during controlled hunts: 5,960 (53% success rate)

How it stacks up

All eyes were on muleys last fall, for reasons stated a billion times already in this recap: severe winter. However, the winter prior to last year’s hunting season was as mild as Norwegian hot sauce and, as predicted, paved the way for some good news in the mule deer hunting department.

A total of 73,748 mule deer hunters successfully harvested 23,898 mule deer—nearly 30% more than 2023. Of those, only 3,380 (or 14%) were antlerless.

That’s important to note here. One might see a 30% increase in overall harvest just 1.5 years after a brutal winter and have some concerns, particularly for eastern Idaho does. Afterall, isn’t the purpose of limiting antlerless hunting to rebuild herds?

Well, that’s exactly what Fish and Game wildlife managers did coming out of last winter. While the winter of 2024 was indeed mild, wildlife managers in eastern Idaho still aimed to give mule deer does and fawns another year of limited antlerless hunting in hopes of bringing those numbers back up. And so far, it appears to be working.

“We are trying to help mule deer populations rebound after the tough winter of 2022-23,” said Boudreau.

Remember, it takes several years, not a year, for mule deer to rebound from harsh winters, especially statewide. Winter severity tends to be inconsistent throughout the state, so one area’s herds might take a hit while others thrive, which can offset each other and lead to similar statewide numbers despite changes in the local herds.

Also note that outside of this eastern Idaho bubble, mule deer numbers statewide have been relatively stable in recent years. Buck harvest, specifically, went up by nearly 5,000 in just a year! And depending on the final results from this year’s winter fawn survival, we could see more of that trend play out in 2025.

WHITE-TAILED DEER

By the numbers

Total white-tailed deer harvest in 2024: 20,908

2023 harvest total: 19,828

Overall hunter success rate: 40%

Antlered: 14,270

Antlerless: 6,640

Taken during general hunts: 19,360 (40% success rate)

Taken during controlled hunts: 1,550 (46% success rate)

Fall 2022 was a low spot for white-tailed deer harvest. The reason for that 10-year low was not bitter cold, but hot, dry weather and biting midges. Epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) wreaked havoc on the Clearwater region’s whitetails that summer, killing an estimated 6,000-10,000 deer. So, to see two consecutive increases in whitetail harvest is a good sign for wildlife managers and hunters alike that whitetails herds are moving back in the right direction.

An estimated 48,766 white-tailed deer hunters hit the woods last year, with 40% of those successfully bagging a deer. Who knows—maybe the same 48,766 hunters went 2 for 2 during the past two years, as harvest success was identical.

As predicted though heading into the 2024 hunting season, overall harvest numbers for whitetails increased from 19,828 to 20,908.

Like with any species, and as mentioned numerously in regard to muleys, it takes time for animals to rebound, but whitetails tend to rebound more quickly. Back in early 2023, Boudreau forecasted “another 2-3 years” before the Clearwater’s whitetail herds would be fully recovered, but optimistically pointed out that they were in fact “over the hump.”

And while the jury’s still out on east Idaho’s mule deer, the verdict on the Clearwater’s white-tailed deer is in: The herds have bounded right back.

With that said, the year ain’t over

Please be mindful that even as April and early May melts snow and the hills begin to green, the deer are still energetically stressed from previous winter conditions and its effect on their bodies. Deer go into the winter with their groceries on their back in the form of fat, and the less they are stressed and pushed around on the winter ranges, even during early spring, the more likely they are to survive.

And sadly, green forage does not mean all fawns will survive their first winter. Overstressed young mule deer can die with bellies full of green forage because their weakened bodies are unable to adapt to the higher nutrients.

Hunters: You make these kinds of insights possible

This might shock a few people, but knowing how many deer and elk get harvested by hunters every year depends on, well, hunters.

Your involvement gives wildlife managers important hunt and harvest information that directly goes into gauging herd health across the state, figuring out where and how much hunting pressure takes place, and ultimately setting seasons and rules for the future hunting seasons.

This is conservation at its core, folks. Nobody’s asking you for GPS coordinates or bullet weight or what flavor Mountain House you packed. It’s did you harvest—yes or no?

Hunters, take pride in knowing you’re doing your part to ensure game populations remain healthy and resilient and ensuring each species will still be there to hunt for your kids, the next generations.

Now, the moment has already come and gone to fill out hunter reports for last fall, but this is a reminder that better information means better management, which in turn can mean more hunting opportunity because a lack of good data can mean shorter hunting seasons and/or fewer tags.

I know it still feels like a century between now and the fall 2025 hunting season, but take this simple reminder and file it away. Make it a tradition every year. Do whatever you think it will take to remind yourself to fill out your mandatory hunter report after next fall’s hunt.

It’s your big game herds, so take pride in how they’re managed and conserved.